Asian American Erasure and Endurance in Agriculture

As part of our Seed Saving and Cultural Memory Banking seminar in Winter 2022, Nina F. Ichikawa, who currently works with the Berkeley Food Institute, gave a presentation titled Asian Americans in food and farming: Erasure & Endurance. She talked about the historical context of AAPI communities in California's food and agriculture that have been shaped by American wars and racism, and charismatically spoke of the work we must continue engaging in today to fight to be seen in our whole.

American imperialism and corporate colonialism through food

Nina researched the food for peace act in the legacy of US foreign aid and how food was being used as a tool for war in Asia in her interdisciplinary studies undergraduate degree at UC Berkeley. She also got to travel to Asia for the first time through the UC study abroad program.

“I sort of got my mind blown to see the other side of the equation because as a fourth-generation American I was always hearing the American narrative of what had happened,” she said. “It really was important for me to leave the country and understand what American food had done to Korea, the Philippines, and also Japan.”

“I just saw these beautiful food traditions that have been around for thousands of years, being obliterated by American junk food companies.”

Nina saw that her tax dollars were helping support that and felt a responsibility as an American to go home and get involved in policy to try to change that and have Americans realize that we “stop shoving our junk food on others because we are really food babies in this country. We really know so little about how to eat, and yet we have the nerve to sell our Big Macs all over the world. Unfortunately many really healthy and long-lasting food traditions are being erased by American policy and American food companies.”

Nina explained that the point of growing so much corn and soy in America is not to feed Americans, it is to capture markets overseas through going to war with them. When these countries lose the war, people are hungry and desperate for food, farmers on the ground are devastated and left with polluted land, and need to start from scratch. The US gives them food for free and then turns them into customers “like a drug dealer.” This is a current American law and it is called the Food for Peace Act. It was also US Department of Agriculture (USDA) policy for many years who have often worked in concert with the US Department of Defense, to open up markets for American agriculture producers in the countries that the United States invaded or had been in military conflict with under the guise of aid and the term ‘we must feed 9 billion.’ “This is based on an imperialist mindset that our food is what's best for those people over there and what's best is if they become our lifelong customers,” Nina said. “That's what it means: to sell to the 9 billion.”

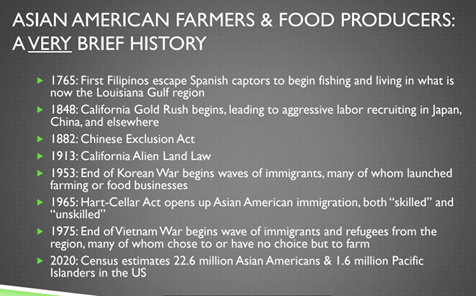

American wars, like the Vietnam war and the CIA’s secret war in Laos and Cambodia, are also linked to the migration of AAPI communities fleeing to the US, where some, like today’s large communities of Hmong farmers in Fresno, CA, became farmers. AAPI groups have faced discrimination, erasure, and also show resilience and self-determination. Part of our project is to tell these stories and histories that don’t get told or much attention in research.

Nina told us about some remembered names in Asian American farming and plant breeding such as: Ah Bing, who bred the Bing cherries, the most commonly grown cherries grown in California today, George Morikami in Florida, and Manabi Hirasaki, who was an especially successful strawberry grower. She brought him up because he was a unicorn of extreme success and extreme wealth and his name is on various monuments, as he was a philanthropist as well and donated to many places, including the Go for Broke Education Center and the Japanese American National Museum in California. Despite these examples of success, every one of these successful Asian Americans still faced discrimination. Ah Bing, when visiting family in China after the Chinese Exclusion Act, was banned from ever returning even though his Bing Cherries got really popular. George Morikami and his farming colony faced many barriers including having all of his assets frozen at the start of World War II, and also soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor that fueled more anti-Japanese racism, the federal government seized over 6,000 acres of their land to create a new military base.

Nina emphasized that these people in history and their stories that are more known are not fair or representative stories of AAPI farmers or even Japanese American farmers because many others may have not become famous, lost their farms, were subjected to the discrimination of World War Two, and never recovered. However, what was important to the success of Hirasaki’s strawberry farming, is that strawberries tie back to the UC system, which for many years in the middle part of the 20th century, had small farm breeding programs to help small and marginalized producers start their farms. Many Japanese American strawberry producers benefited from this program, getting free seeds from UC Davis and other UC campuses that were bred specifically for small farming conditions. Families were able to get an economic foothold after the devastation of the concentration camps, sometimes due to seeds and other support by California’s public university system. Today, many people do not know that such a program used to exist, and they also aren’t prominent in the US anymore. These programs were vital, and Nina says that they can have a similar transformative effect on supporting small and marginalized farmers today if we make it happen. One way we could materially do some justice and uplift and support AAPI farmers today could be through programs that offer assistance with what farmers are struggling with, such as with land and wealth distribution.

“With the wealth generated by the strawberries, we have to understand that this is our collective wealth as California, and we should ensure that it's shared with immigrants, people that don't speak English, people that look different from us, because that's our public education mission, I believe,” Nina said.

The few people talked about in this article have only been a few stories of so many and a much bigger picture of histories to uncover. Even for Nina and the larger community of people in academia, there is still a lot to research and understand. Our fight against marginalization and erasure is ongoing, and today, teaching and learning about stories like these are still pushed away with narratives of controversy, and calling it critical race theory. “But it's really not critical race theory, it's American history and sadly just too many of ourselves and our neighbors and friends are really ignorant of this history,” Nina said. The US education system needs to tell more of these untold histories of so many marginalized groups in America to represent all of us, as we are Americans too, having contributed so much to our food system at the very least. Many AAPI groups have been Americans for centuries, and even those that have only been Americans for decades have often spent every year of that time working in food in the United States.

“We're still being erased but we're still enduring, we're still surviving, we're here and building a new generation and trying to carry on our traditions,” Nina said.

We need to revisit past history but also be part of the active fight for the history in the present that is constantly in danger of being erased. Without this contestation, many people and institutions do not care for it or are against bringing covered up histories to light. Some ways people can do this are by writing about it as journalists, speaking about both past and current history in conversations, taking ethnic studies classes, which can connect people to talking to people involved in this work, and doing personal research. The last few years of anti-Asian racism have also awakened many like myself to the internalized model minority myth—and knowledge is power. Nina said: “It's not just an inconvenient compliment to say certain Asian Americans are smart or have done well. It's really a tool to further white supremacy and entrench racial border lines, so I think that when we talk about food and farming, this is also time to really talk about all the ways that we've succeeded and prospered and all the ways that we've suffered and failed that's part of the story, as well.”

Nina hopes that her presentation gives people a start to do more of their own research and thinking, and calls for people to be part of this meaningful fight. “If you like things to be current and exciting then history is a great place for you,” she said.

A book recommendation, where Nina wrote a chapter for:

Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader (2013: NYU Press)